SUPPORT

THIS SITE!

Site

map

Site

update log

About

this site

Mailbox

Author thanks

Galina Sergeeva at Tsiolkovsky museum in Kaluga and Elena Timoshenkova,

a granddaughter of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky for their help in preparing

this section.

|

Tsiolkovsky

and bolshevism

Tsiolkovsky

died famous and respected in his native land. During the Soviet period,

Tsiolkovsky was portrayed as the brilliant scientist from the Russian

heartland who struggled to get recognition from the ignorant and indifferent

officials of czarist Russia. It was only after the Socialist Revolution

that Tsiolkovsky "experienced essentially a second creative birth,"as

one Soviet history put it. In reality, Tsiolkovsky's claim to fame as

the man who first proposed the use of rockets for space travel rests largely

on work done before the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, and it took Bolsheviks

some time to appreciate his unorthodox ideas and not consider them a threat

to their own revolutionary goals.

Documents

made public in the post-Soviet Russia revealed that Tsiolkovsky’s

path through the political and social cataclysms of revolutionary Russia

was not as trouble-free as the official Soviet histories painted. "Like

any other person who was brought up in a totally different world, he had

a problem understanding what was happening," Galina Sergeeva says.

"On one hand, the goals which the Revolution declared — the

happiness and well-being of the people, the reconstruction of the world

for the better — he obviously supported. But on the other hand, he

suffered almost immediately (after the Revolution): ChK (the Bolsheviks'

notorious secret police) arrested him, brought him to Moscow, and threw

him in prison."

According

to Sergeeva, Tsiolkovsky was accused of anti-Soviet writing and was jailed

in the infamous Lubyanka prison for several weeks before a high-ranking

official had him released. (At the end of the 20th century, the local

branch of the Russian security service transferred historical documents

related to the scientist's arrest to the Tsiolkovsky Cosmonautics Museum

in Kaluga.)

Apparently,

the Soviet government had "re-discovered" Tsiolkovsky in 1923,

in the wake of the publication of Hermann Oberth's "The Rocket into

Interplanetary Space." In response to international resonance generated

by Oberth's proposals to use rockets for space travel, the Soviet press

pitched Tsiolkovsky as a true pioneer of the space flight theory. The

campaign was in-line with the Soviet practice of "finding" the

Russian inventor for each and every discovery from steam engine to airplane

to radio. However, unlike Cherepanov brothers, Mozhaisky and Popov, Tsiolkovsky

was recognized around the world as the father of the space flight theory.

After

his recognition by the Soviet authorities, Tsiolkovsky's works were widely

published and popularized, the government granted him a pension, and he

and his family were given a new house in Kaluga, where his descendants

had lived a century later.

However,

even after the Soviet government embraced Tsiolkovsky as a hero, it essentially

silenced him as a philosopher. Although Tsiolkovsky often criticized traditional

religions for their "primitive" explanation of the world, he

himself saw the universe in almost theological terms, as a higher being

that controls life on Earth and beyond. "We are at the will of and

controlled by Cosmos," he wrote in a work titled "Is There God?"

"There is no absolute will — we are marionettes, mechanical

puppets, machines, movie characters." Obviously, such ideas did not

fit well with official Marxist ideology, even with Tsiolkovsky's painful

efforts to reconcile his quazi-religious thinking with scientific reason.

Despite increasing intolerance of the Soviet system toward any deviation

from the official doctrines of the Communist Party, Tsiolkovsky until

his last days strived to advance his unorthodox views of the Universe and

the role of humans in it.

"I

put all my efforts into the work, which I have little hope to publish

or complete," Tsiolkovsky wrote during this period, "There is

total indifference toward my work in the society, and even (my) books

are not distributed. There is no money for publications, besides other

obstacles... It is clear why they are silent about my philosophy, it is not

in fashion anymore, to say the least."

Three

months before his death Tsiolkovsky told his daughter and assistant, Lubov

Tsiolkovskaya that he had a number of articles, which could comprise a

book. It became known as "Ocherki o Vselennoi" (Essays On the

Universe), the work which summarized the evolution of Tsiolkovsky's phylosophical views, presenting man as a part of the cosmos and its destiny to explore

space and contact alien civilizations.

This work was published in Russia in 1992, or 57 years after

death of its author and only one year after the collapse of the Soviet

Union.

|

Tsiolkovsky

and F. N. Ilyin, the chairman of central soviet of the state-sponsored

Society for the Advancement of Aviation and Chemical Sciences, Osoaviakhim.

Credit: Kaluga Museum of Cosmonautics

Tsiolkovsky

(left) along with Soviet and Communist Party officials participates in

the "Defense Day" in Kaluga on May 18, 1934. Credit: Kaluga

Museum of Cosmonautics

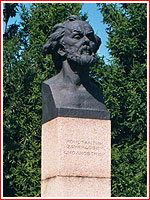

Monument

to Tsiolkovsky in Moscow. Copyright © 2000 by Anatoly Zak

Monument

to Tsiolkovsky unveiled in Izhevskoe on September 17, 1977, the scientist's

120th anniversary. Copyright © 2001 by Anatoly Zak

|