|

|

|

||||||||||

Soviet probe makes world's first soft landing on the Moon On Feb. 3, 1966, after many failed attempts, a Soviet robotic lander accomplished the world's first soft landing on the surface of the Moon and lived to tell about it. The pioneering mission finally dispelled old fears that a visiting spacecraft could drown in a thick layer of lunar dust. As the Luna-9 (E6) spacecraft began transmitting the first images from another world, the invisible race to decipher the precious information began simultaneously in the USSR... United Kingdom and the United States!

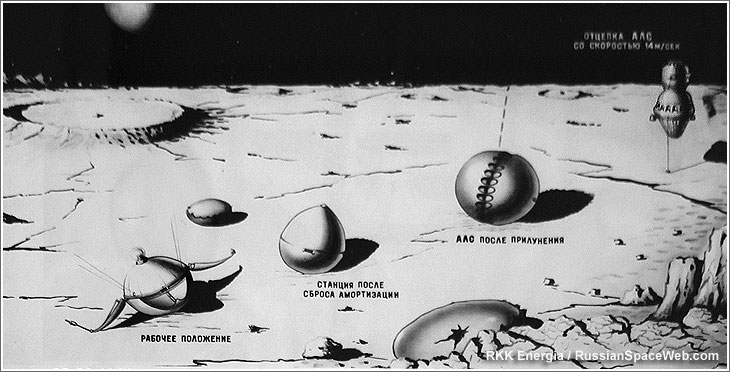

Flight scenario and key milestones of the Luna-9 mission.

From the Earth to the Moon The USSR's 12th attempt to conduct a soft landing on the Moon was launched on Jan. 31, 1966, at 14:41:37 Moscow Time. The 8K87M rocket No. U103-32 (later known as Molniya-M) lifted off from Site 31 in Tyuratam, carrying the E6 spacecraft (serial number No. 13/202). After reaching a 224 by 173-kilometer parking orbit around the Earth with an inclination nearly 52 degrees toward the Equator, the Block-L upper stage fired, sending the 1,583-kilogram probe toward the Moon. The mission was officially announced as Luna-9. Measurements of the probe's actual orbit conducted during the night from January 31 to February 1 showed that it was on a flyby trajectory passing around 10,000 kilometers away from the Moon around 3.5 days after liftoff. Based on that data, ground controllers programmed the spacecraft to conduct a trajectory correction maneuver on February 1, 1966, at 22:29 Moscow Time. The engine firing pushed the vehicle from a flyby trajectory to a collision course with the Moon. After the successful maneuver had been completed at a distance of around 233,000 kilometers from the Earth and 190,000 kilometers from the Moon, the spacecraft was spin-stabilized. On February 3, around an hour before hitting the Moon and 8,300 kilometers from its destination, Luna-9 successfully oriented itself with its tail down. Also, a pair of soft-landing bags of the lander were inflated and the two no-longer needed avionics containers were jettisoned from the spacecraft. At an altitude of 75 kilometers above the Moon, and just 48 seconds before reaching its surface, the probe fired its braking engine on a command from its altitude-measuring antenna. (770) Western listening posts monitoring doppler shift from the probe's radio signals detected a rapid slowdown of the vehicle beginning at 18:44:09.5 GMT. All signals stopped at 18:45:05 GMT. (769) The Moon landing

Landing scenario of the Luna-9 mission. As it transpired later, at the final phase of the Luna-9's landing, the main engine was cut off at an altitude of around 150 meters and the spacecraft continued its descent under the thrust of four vernier engines. At an altitude of around five meters, the 100-kilogram ball-shaped lander split itself from the rest of the spacecraft on a command from a special probe extended from the vehicle. According to the Soviet announcement, Luna-9 successfully landed on Feb. 3, 1966, at 21:45:30 Moscow Time on the eastern edge of the Ocean of Storms (Oceanus Procellarum). The local morning landing time was chosen to provide the best temperature conditions for onboard equipment and for TV imaging. (770) The lander hit the surface inside an inflatable cocoon with an impact speed estimated between four and seven meters per second. The inflatable air bags were programmed to jettison from the lander four minutes after the touchdown, followed by a 10-second deployment of the lander and the unrolling of its antennas. Sure enough, at 18:49:45 GMT, western listening posts heard again from the Soviet spacecraft. (A command from the ground to release air bags could also be used if needed.)

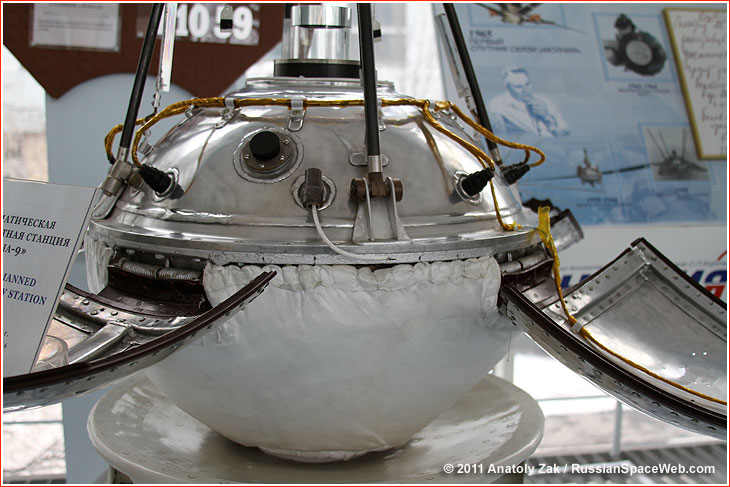

A museum replica of the E6 spacecraft in deployed position. February 4 According to the Soviet TASS news agency, on February 4, Luna-9 was in contact with ground control for a total of three hours 20 minutes during four communications sessions. At 04:50 Moscow Time, a signal from the ground commanded the lander's camera to begin a scan of the surrounding landscape and transmitting images back to Earth. More communications sessions were planned from 18:40 Moscow Time on the same day and on February 5 at 04:00 Moscow Time, TASS said. During the communications session on February 4, from 18:30 to 19:55 Moscow Time, Luna-9 transmitted a 360-degree panorama of the lunar surface with a vertical view angle of around 30 degrees. In addition, ground control sent commands to the spacecraft to conduct detailed imaging of certain areas selected by the scientists, TASS said, promising to publish the imagery in the near future. February 5-6 According to TASS, the first communication session of the day, starting around 04:00, was dedicated to the telemetry transmission. The pressure, temperature and voltage onboard the spacecraft were within acceptable parameters, the official Soviet agency said. The next communications session was scheduled for 19:00 Moscow Time, which would conclude the planned research program onboard Luna-9, TASS said, hinting that the spacecraft was about to run out of power. The next official release confirmed that the lander was in touch with ground control from 19:00 to 20:41 Moscow Time, concluding the planned program. Still, the next day, another official report announced that thanks to remaining power in onboard batteries, an additional two-hour session had been held with the spacecraft beginning at 23:37 Moscow Time on February 6. During this final contact, both telemetry and new photos of already imaged areas had been received. During the session, practically all remaining power resources of the spacecraft had been exhausted, ending its operation, TASS announced. According to TASS, a total of seven communications sessions with the spacecraft lasted eight hours five minutes. (770)

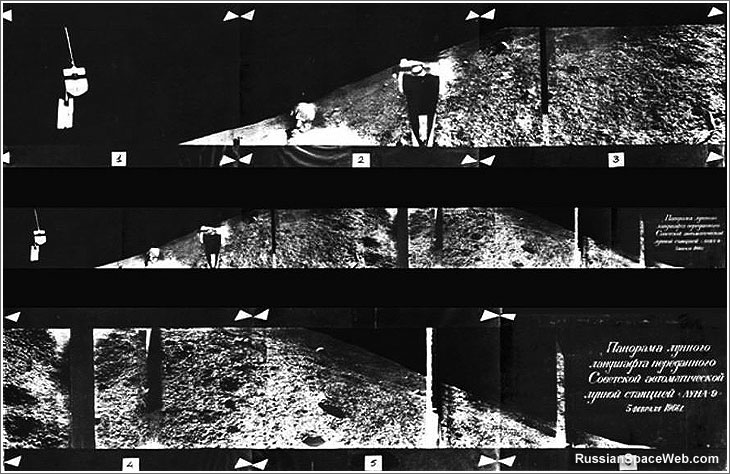

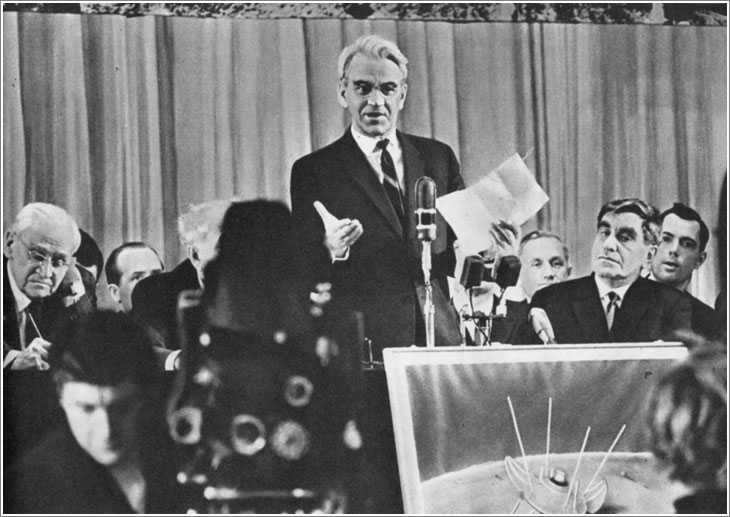

Panoramic images of the lunar surface from Luna-9. Scandal around images During the mission of Luna-9, a total of 40 square images were transmitted back to Earth. (767) Details as small as one or two millimeters in size could be resolved in areas nearest to the camera. The spacecraft appeared to be sitting on a largely flat plane with a horizon around 1.5 kilometers away. Photos of the same areas taken at different time revealed changing shadows as the Sun moved across the lunar sky. As a result, scientists could make a detailed profile of the landscape and determine size and shape of rocks and craters. (766) Ironically, astronomers at Jodrell Bank observatory near Manchester, UK, were the first to publish intercepted images from Luna-9 on February 4, though in distorted form. Chained by secrecy and bureaucracy, Soviet scientists were able to present properly formatted images only a day later, along with their consternation toward their enterprising colleagues abroad. On February 10, Soviet scientists held a triumphant press-conference chaired by the head of Academy of Sciences Mstislav Keldysh on the results of the Luna-9 mission.

Mstislav Keldysh presents results from the Luna-9 mission. The US impact Since the veil of secrecy has been lifted from the Soviet space program at the end of the 1980s, the most significant information on the history of the Luna-9 mission actually came from the US. As recently unclassified documents reveal, the mission of Luna-9, as well as the failed attempts of its predecessors to make soft landing on the Moon, attracted very close attention from American intelligence services. They correctly perceived Soviet probes as possible precursors to a manned landing or even to a permanent lunar base. Along with the British radio astronomers and the Soviet ground controllers, US telemetry analysts at the National Security Agency, NSA, (among several other organizations) listened to transmissions from Luna-9 from its liftoff. Soon after the spacecraft reached the Moon on February 3, a routine flow of telemetry from the probe was complemented with a new type of signal. It was easily identified as a photo-facsimile transmission similar to those used for wire photo services on Earth. The image transmission continued as late as February 6 in the United States. (769) On February 4, the NSA scrambled to figure out how to reproduce the priceless imagery. When some of the NSA officers expressed skepticism at the possibility of printing the actual photos, one of their superiors said that "the entire White House and Congress were looking to NSA for answers and we were not producing." Fortunately, a young electrical engineer John O'Hara from the telemetry division of the NSA sketched a possible solution combining his own hardware with existing recording equipment from the NSA's contractor Honeywell. Early in the afternoon, the NSA officers were able to improvise the process, however an initial attempt to print pictures produced just gibberish. The spectral analysis of the signal indicated that its frequency had to be adjusted to be readable by available hardware. O'Hara hastily fashioned another piece of electronics to correct the signal. The new printing attempt finally produced images from the Moon, though with the wrong proportions. One image showed what analysts believed was a foot of the lander. The image was clear enough to resolve Russian letters and numbers. To the relief of NSA officers, these were just meaningless serial numbers, not taunting messages for the Americans. Like their Russian colleagues, US analysts noticed changing shadows on different photos of the same areas as the Sun moved across the lunar sky. The photos also revealed that the spacecraft had moved slightly from its initial position on the surface, possibly as a result of shifting soil below it. In order to resolve the problem with the aspect ratio of printed images, O'Hara had to circumvent the normal bureaucratic and secrecy process to obtain a recorder with an appropriate speed from Honeywell. By the morning of February 5, the NSA was able to produce perfectly sized images from Luna-9 and that afternoon, they were reportedly on the desk of President Lyndon Johnson! No doubt, Soviet pictures provided a powerful incentive for the White House to press ahead with the Apollo program, aimed to land a man on the Moon. The agency's security bosses later attempted to charge O'Hara with "exceeding his authority" but the case was dropped after the intervention of Charley Travis, the head of Director's Advisory Group on the Electronic Reconnaissance at the NSA. (768) On Jan. 21, 2026, the Nature magazine published results of a study that used computer learning method to analyze images from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, LRO. The spacecraft has been imaging the Moon with a resolution from 0.35 to one meter per pixel since 2009 and produced a large archive of high-resolution surface photos, which were detailed enough to discern space hardware but were too numerous for manual searches. Using a computer model, known as YOLO-ETA (for You Only Look Once – Extra-Terrestrial Artifact) to analyze the LRO photographs, the authors of the study reported "several high-confidence detections of artificial objects" near 7.03 degrees North latitude, –64.33 degrees East longitude, which was within the five-by-five-kilometer area, where Luna-9 had believed to be landed in 1966. Soon thereafter, a nearly year-long effort by Russian educator Vitaly Egorov, helped by an informal group of volunteers, also yielded what he believed to be the Luna-9 lander on the surface of the Moon. Egorov and other enthusiasts pinpointed the elusive spacecraft after poring through the archive of photos produced by LRO. Photos from LRO previously revealed several other spacecraft on the lunar surface, but all previous attempts to locate Luna-9 based on the coordinates announced by the USSR after its historic first soft landing on Feb. 3, 1966, were fruitless. The ultimately successful search in 2025 put the long-defunct lander 25 kilometers from the officially declared point. The cruise/braking stage of the lander, which split from it at touchdown, was found 750 meters to the East from the main spacecraft. Although presumed hardware from the historic mission is barely distinguishable on the LRO photos, Egorov tied the location to a number of landmarks visible on the panoramic photos from Luna-9. According to Egorov, he hoped that the Indian Space Agency could corroborate LRO's images with more detailed photos from the Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft orbiting the Moon. Presumed locations of the Luna-9 spacecraft and its cruise stage:

|

|

||||||||||