More on Phobos-Grunt: Project developments in 2004-2009 Command and control challenges in Phobos-Grunt mission In the aftermath of Phobos-Grunt Searching for details: The author of this page will appreciate comments, corrections and imagery related to the subject. Please contact Anatoly Zak. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

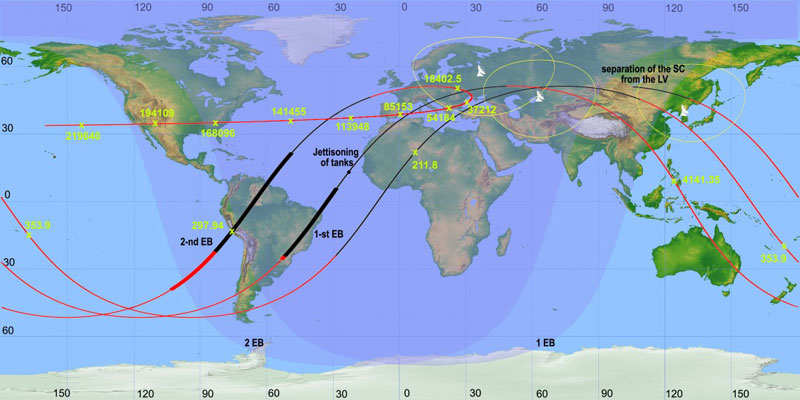

| Above: An initial trajectory of the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft including its first three orbits and the escape path toward Mars. Thick lines show periods during engine firings (red in daylight; black - in the shadow); green numbers indicate distance from the Earth surface in kilometers; green circles show the range of Russian ground control stations (left to right) in Shelkovo (Medvezhi Ozera) near Moscow (left), in Baikonur (center) and in Ussuriysk (Far East)(right). Shaded areas show the position of the Earth's shadow during the first (right) and second (left) engine burn. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After a two-decade break in the exploration of the Solar System, Russia launched a risky mission to land on the mysterious Martian moon, Phobos, and to return samples of its ancient soil back to Earth.

Previous chapter: Phobos-Grunt preparations during 2011 Launch!

A two-stage Zenit rocket (Zenit-2SB41.1) lifted off from Site 45 in Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan, on Nov. 9, 2011, at 00:16:02.871 Moscow Time (20:16 GMT, 3:16 p.m. EST, on November 8), or a fraction of a second earlier than the previously announced launch time of 00:16:03.145. After a vertical ascent from the launch pad, the Zenit rocket headed eastward along a usual path to enter orbit with an inclination 51.4 degrees toward the Equator. The live TV broadcast of the launch was cut off around the time of the second stage separation, however an initial parking orbit for the payload was confirmed shortly afterwards. The separation of the spacecraft from the second stage took place at around 00:27 Moscow Time, or 688 seconds after a flawless liftoff. After the separation of the Zenit's second stage, Phobos-Grunt was left in an elliptical (egg-shaped) orbit with a perigee (lowest point) of 207 kilometers above the Earth surface and an apogee (highest point) of 347 kilometers. As it became known days later from an unofficial source, the fact of separation between the rocket stage and its payload as well as their initial orbits had been tracked by ground control and confirmed by the telemetry from the Zenit's second stage and during a short communications session via a C-band RPT111 transmitter onboard Phobos-Grunt. The communication with the spacecraft via RPT111 was maintained during the first orbit and the tracking of the spacecraft was conducted via an RDM 38G6 receiving and transmitter system. Between 01:48 and 01:54 Moscow Time, a small antenna at NPO Lavochkin in Moscow was receiving normal telemetry from Phobos-Grunt. Telemetry from the spacecraft showed that all its onboard systems had been in operational condition: solar panels had been deployed and the orientation and stabilization system, SOiS, correctly oriented the spacecraft toward the Sun, to ensure recharging of the onboard batteries. The onboard computer, BVK, and the optical solar sensor, OSD, were functioning and onboard batteries on the cruise stage, BA PM, were charging. A pair of star orientation trackers, BOKZ-MF, remained turned off at the time, because according to the flight program, they were supposed to be activated later (on the night side of the orbit). After a 1.7-orbit coasting flight, lasting 2.5 hours, the engine onboard the probe's MDU propulsion unit was to be activated to boost the spacecraft into a 250 by 4,170-kilometer orbit. It would take Phobos-Grunt 2.2 hours to complete a single revolution around the Earth at this altitude. After 2.1 hours in passive flight, the MDU unit would fire again to send the spacecraft on its way to Mars. Soon after Phobos-Grunt reached its initial orbit, NASA posted a report on its web site claiming that the current ISS crew would "be able to view Phobos-Grunt starting at ~7:58 p.m., at a range of 3248 nmi., with the spacecraft and its exhaust plume in sunlight for the entire duration of the viewing opportunity and the ISS in eclipse (darkness)." However, since the report mistakenly claimed that the launch of Phobos-Grunt would take place at 7:16 p.m. EST, it was unclear what phase of the flight would be visible from the ISS. In its usual tradition of "simplifying" Russian spacecraft names, NASA identified the mission as The Phobos Sample Return Mission, PhSRM. The note also erroneously stated that the Zenit rocket in the Phobos-Grunt mission included a Fregat upper stage. Disaster strikes Following the liftoff, Roskosmos limited its "coverage" of the mission's risky initial phase to two sentences about the successful launch, however it provided no updates on the status of orbital maneuvers in time for critical engine burns. During the entire night of November 8 and early morning of November 9, the web site of NPO Lavochkin, the spacecraft's prime developer, featured "news" about preparations for the mission and awards to the company's workers. Official Russian media, which avalanched the Internet with headlines about the successful launch, were also eerily silent about the post-liftoff status of the mission. Thus, Russia's first 21st century planetary mission was circling Earth in the state of a virtual informational blackout. Then, at 00:05:16 GMT, Ted Molczan, a prominent satellite observer, reported that the spacecraft had not changed its orbit as it was predicted to do at the end of the first planned engine burn, while a separate Russian source reported that no telemetry was coming from Phobos-Grunt. As the first two burns were to be conducted fully autonomously according to a pre-programmed sequence, there was practically no hope that further maneuvers could fix the situation if it had developed as reported. A message board set up by the Academy of Sciences specifically for the mission preceded the launch with a posting, stating that the mission had been covered timely and regularly in specialized monthly magazines! As problems in orbit became known, the forum seemingly had no official updates or even an active moderator. Its glaring vacuum was quickly filled with bizarre postings, including those signed, V. V. Putin, spewing profanities toward Russian scientists and foreign visitors who were fruitlessly inquiring about the status of the mission. A poster on the NASASpaceflight web forum reported citing a source at NORAD that a deep-space antenna at Goldstone, California, had detected a signal from Phobos-Grunt. According to this information, the spacecraft was transmitting telemetry via all available frequencies, a clear evidence of problems onboard. Before launch, the spacecraft was programmed to point its antenna northward in case of problems prior to critical engine firings over the South American region, to facilitate contact with ground stations in US, Europe and Russia. According to available data, the spacecraft was in a so-called "safe mode," which indicated problems, but left some hopes for further attempts to fire its engines. The MDU propulsion unit designed to go with the spacecraft all the way to Mars would be capable of a prolonged contingency mission. Along with the Goldstone antenna, a European ground station also received some unreadable signal from the spacecraft. There were some indications that the probe's solar panels had not been pointed toward the Sun by the time the charging of batteries had been commanded by the onboard computer. In the meantime, eyewitnesses in Brazil reported seeing what looked like engine firings apparently associated with the Phobos-Grunt mission. Obviously, at that distance, even if it was indeed the right object, any flashing of the spacecraft's solar panels or other reflective surfaces could be confused with the action of the propulsion system. As it transpired later, after two initial orbits, ground control could not locate the spacecraft along the flight path predicted before launch based on orbital parameters, which it was suppose to have after the completion of its first engine firing. After several hours of search, tracking facilities had finally located Phobos-Grunt in its original parking orbit. It was possible to confirm that the probe's external tank remained attached to the propulsion unit, however no telemetry was coming from the spacecraft and no signals from the RDM receiver-transmitter could be heard. Much of critical data on the orbital parameters of the Phobos-Grunt mission apparently came from Russia's military SKKP tracking network. As early as 02:05 Moscow Time, (or during a second orbit and two hours after launch), the network's command center was able to distinguish between the spacecraft and its upper stage, as well as calculate more or less accurate orbits for both. As Phobos-Grunt flew again within the range of ground control stations from 03:20 to 03:35 Moscow Time, all further observations were matched to this orbit. With several minutes of delay for data processing, a final confirmation that the spacecraft had not performed any orbital maneuvers and had remained in its original orbit was made around 03:45 - 03:50 in the morning. Finally, at 06:13 Moscow Time on Wednesday, November 9, RIA Novosti quoted the head of the Russian space agency, Vladimir Popovkin, admitting that none of two planned engine firings of the MDU propulsion unit onboard Phobos-Grunt had taken place. "We had a difficult night, we could not locate the spacecraft for a very long time, now we know its coordinates," Popovkin said. According to Popovkin, the spacecraft possibly failed to establish a correct orientation in space either via Sun-based attitude-control system or via star trackers (after entering Earth's shadow), thus preventing the formation of the automated command to fire the propulsion system. He stressed that the situation was not nominal but not unpredicted and there were recovery procedures in place. Popovkin said that it would be possible to re-upload the programming sequence onboard the spacecraft and no propellant, including supplies for the first maneuver inside the jettisonable external tank, had been spent. Ground controllers reportedly had three days to uplink new instructions onboard the spacecraft, before onboard batteries would be fully discharged, Popovkin said. This statement apparently indicated that the spacecraft would not be able to use its solar panels to recharge batteries. Moreover, another source quoted by RIA Novosti said that the questions still remained whether problems with orientation had been the result of software or hardware problems. While software issues could be "patched" from the ground, the failure of attitude control sensors or other critical systems would likely doom the mission. On November 9, at 01:17 Moscow Time, a project representative reported that telemetry from the spacecraft had been received, confirming that onboard batteries had been recharging and the spacecraft had been oriented toward the Sun. Russian military tracking assets and NASA ground facilities were reportedly involved in the effort to track the mission. Only on the afternoon, November 9, did Roskosmos issue an official press-release stating that first two post-launch contacts with Phobos-Grunt had showed normal operations of the spacecraft according to the flight plan. However engine firings planned beyond the range of ground stations had not taken place. "Currently, all necessary parameters of the spacecraft motion have been determined," the statement said, however due to the low orbit of the spacecraft it would not reenter the range of Russian ground stations until 23:00 Moscow Time (14:00 EST) on November 9. Based on the analysis of data, Roskosmos promised to prepare and upload onboard all necessary commands for the resumption of orbital maneuvers. Most importantly, the agency assured that a more accurate estimate of the mission's orbital parameters and power supplies onboard the spacecraft had provided two weeks for the transmission of new flight instructions to Phobos-Grunt. At 16:35 Moscow Time (7:35 EST), a poster on Astronomy.ru web forum reported that new attempts to escape Earth orbit would be conducted between 03:00 and 05:00 Moscow Time on Thursday, November 10 (6 p.m. - 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday). According to the Interfax news agency, Phobos-Grunt was expected to enter the range of Russian ground control stations at around 21:30 Moscow Time (12:30 p.m. EST), however only a ground station in Baikonur was equipped to downlink all necessary telemetry data and transmit new commands for the upcoming maneuver. Although the spacecraft was expected to remain in orbit for at least 10 days before reentering the Earth atmosphere, in just two days it would descent too low for the available propellant to raise its parking orbit and conduct another attempt to enter escape trajectory toward Mars, some unofficial reports said. However, RIA Novosti quoted an unnamed space official as saying that the spacecraft could "safely" remain in orbit from one week to up to a month. However whether the mission would be safe to resume during this entire period was not specified. In early hours Moscow Time, the editor of this web site received a message from the director of Moscow-based Space Research Institute, IKI, Lev Zeleny, informing that tracking facilities of the US military provided significant help in establishing exact orbital parameters of the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft. This data was to be used during the previous night to send commands to the spacecraft as it was passing within range of ground control stations. Zeleny reassured that the mission team still had had "few days for reprogramming before the end of the Mars accessibility window for 2011." At 06:20 Moscow Time, Vesti TV channel reported that ground controllers successfully downlinked information from Phobos-Grunt and started its analysis to develop correction actions. However multiple sources on Russian online forums, including at the official board of the Phobos-Grunt mission said at 01:46 Moscow Time that several attempts throughout the night to communicate with the spacecraft had not been successful, including the use of specialized uplink hardware in Baikonur. As a result, the cause for the failure of the mission to leave Earth orbit remained a mystery. New attempts to send commands to Phobos-Grunt were scheduled for 18:00 Moscow Time (9 a.m. EST). In the meantime, a poster on the Novosti Kosmonavtiki forum reported some crucial details on the very initial phase of the mission. As it transpired, immediately after reaching the orbit, telemetry was received from the second stage confirming normal separation of the rocket and the spacecraft. During the second orbit, ground control received the only communication from the spacecraft itself, confirming that solar panels had been deployed, the vehicle acquired correct orientation toward the Sun and all systems had been functioning well. However after the second orbit, the spacecraft was found in orbit transmitting no signals and no telemetry came during the previous night. At a ground station in Baikonur, ground controllers attempted to re-boot Phobos-Grunt's flight control computers, BKU, and were planning to repeat the same attempt during the upcoming night. According to one theory, the spacecraft's flight control computer reset itself to a pre-launch state, awaiting a signal to re-initiate its flight program. During the day, ground stations of the European Space Agency, ESA, located in Australia and in Kourou also attempted to communicate with Phobos-Grunt, apparently without any success. The Kourou station was scheduled to contact the probe around 11:40 GMT (15:40 Moscow Time). As one informed source on the Novosti Kosmonavtiki forum reported the main problem with controlling the spacecraft had stemmed from the fact that the probe's low-gain antennas might've been obstructed by the external tank of the MDU propulsion unit, thus preventing signals from the ground reaching the flight control computers. In the meantime, the probe's high-gain antenna was in folded position at that phase of the flight. To make the situation worse, for some unknown reason, the spacecraft would not downlink telemetry to the ground either. In the meantime, Russian ground controllers were preparing for yet another round of attempts to communicate with the spacecraft during evening hours of November 10 and early hours of November 11. Around 23:00 Moscow Time, Phobos-Grunt reappeared over Baikonur and, according to some unofficial reports, ground controllers sent a signal to activate probe's onboard transmitter, which was designed for radio-measurements of its trajectory. The command was apparently sent directly to the device, bypassing other systems. However, yet again, no carrier signal from the transmitter could be heard. Further attempts were promised overnight. All efforts to contact Phobos-Grunt proved futile and the attention of the press was quickly switching to the inevitable uncontrolled reentry of the spacecraft into the Earth atmosphere, expected sometimes from the end of November to the middle of December. NORAD reportedly projected the reentry of the spacecraft on November 26. The window of opportunity for the mission's departure to Mars was expected to close on November 20. According to known technical specifications of the Phobos-Grunt mission, the 13-ton vehicle contains more than 10 tons of toxic propellants - unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (fuel) and nitrogen tetroxide (oxidizer). Although most of the fuel and oxidizer would burn during the initial phase of reentry, the size and mass of the spacecraft practically guarantees that surviving metal debris would reach the Earth surface. In addition, a capsule for soil samples designed to survive a hard landing would be reentering alongside the spacecraft. Due to its insulated design, the capsule would likely be torn off from the rest of the vehicle early into the reentry and its impact would likely take place away from the rest of the debris along the reentry path. The crash could take place anywhere from 51.4 degrees North latitude to 51.4 degrees South latitude. In the meantime, a moderator on the online forum of the Novosti Kosmonavtiki magazine posted excerpts from a two-volume technical description of the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft published by its manufacturer, NPO Lavochkin. From the available information on the mission scenario it became clear that all operations onboard the spacecraft during its transfer from the initial parking orbit to the transfer orbit had been designed to be conducted exclusively under automated control and no two-way communications with ground stations would be possible. As a result, current attempts to control the spacecraft in its parking orbit were completely improvised. Still, one participant in the project maintained without much details that establishing control over the spacecraft was possible. Several independent observers reported seeing Phobos-Grunt moving across the sky without discernable flashing -- a possible evidence that the probe's attitude control system was keeping it from tumbling in space. In the meantime, latest data from NORAD showed that instead of expected 215-meter loss of its orbital altitude, the spacecraft actually slightly climbed upward by 138 meters by the end of the day on November 10. Thus, a perigee (lowest point) of its orbit got a total increase of under 300 meters and an apogee (highest point) stopped its decay. During November 11, further slight increase in the perigee and in an inclination of the orbit toward the Equator became discernable in orbital parameters. The phenomenon could be a result of inaccuracy in measurements, but also a possible indication of some propulsion activity, such as attitude-control thruster firings or propellant leaks. All attempts to establish contact with the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft made by Russian and European ground controllers during the night from November 11 to November 12 proved fruitless once again. By November 13, Phobos-Grunt stopped its mysterious thrust upwards, a leading satellite observer, Ted Molzcan reported based on published data from the US tracking radar. The spacecraft's orbit resumed its slow natural decay, dropping by around 1.2 kilometers of altitude along a semi-major axis. According to Molzcan, Phobos-Grunt would reenter the atmosphere on Jan. 12, 2012. During the day, the anemic probe passed some 80 kilometers from the International Space Station, however due to difference in orbital planes of two vehicles, the relative speed had probably been very high during the rendezvous, leaving residents of the outpost little time to see the probe, even if they tried to do so. A journalistic task of getting in contact with Roskosmos turned out to be as difficult as communicating with a stranded Phobos-Grunt itself. The agency's web site had posted no updates on the mission since the launch day. A web site of NPO Lavochkin had not even announced the launch and their representatives nowhere to be found. According to one respected Russian space journalist, he called the press-office at the company and explained them the situation with the spacecraft! Semi-official Russian news agencies continued quoting contradicting and sometimes bizarre statements from “unnamed industry officials,” some of which could be tracked back to speculations on popular web forums. Following the successful launch of the Soyuz TMA-22 spacecraft in the early hours of November 14, the head of Roskosmos, Vladimir Popovkin, had to face journalists during a traditional post-liftoff press conference. Not surprisingly, he was showered with questions on the fate of Phobos-Grunt. Popovkin admitted that chances of salvaging the mission had been low, but further attempts to communicate with the probe would continue until the closing of the window for departure to Mars at the beginning of December 2011. This statement contradicted previous reliable reports that the last possibility for Phobos-Grunt to escape the Earth orbit toward Mars would be on November 20. Moreover, the precession of the probe's parking orbit made its departure toward Mars impossible after first few days in orbit. (Possibly, some later departure would be possible with a sacrifice of propellant previously reserved for other tasks in the mission.) It would also make sense to continue efforts to recover all possible data from the spacecraft until its reentry, so that the disastrous mission could at least help to design better spacecraft in the future. According to Popovkin, if all efforts to save the mission fail, Phobos-Grunt would plunge back to Earth around January 2012, with little or no debris reaching the Earth surface due to the explosion of 7.5 tons of propellant in the upper atmosphere. Popovkin reiterated that until present, the culprit (which prevented the firing of the MDU propulsion unit) had not been understood due to lack of communications with the spacecraft. Still, ground controllers had been continuing efforts to reload the probe's software and resume flight program, Popovkin said. He also confirmed previous reports that the spacecraft had maintained its orientation toward the Sun (which allowed the recharge of onboard batteries and the survival of all other crucial systems). However the probe's transmitter apparently remained silent. In addition to their efforts to activate the telemetry transmission system onboard Phobos-Grunt, ground control specialists have continued efforts conducted during the past several days to modify the operation of the Spektr-Iks antennas in order to adapt them for the unforeseen task of communicating with the spacecraft in such a low Earth orbit. (530) In the meantime, the space station crew reported that all attempts to photograph the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft in orbit were unsuccessful, due to a very long distance between two vehicles, said cosmonaut Sergei Volkov, who tried to take a picture. Even during a relatively close rendezvous, the separation between the outpost and the probe was 120-150 kilometers. On the night from November 15 to November 16, a ground station in Ussuriisk in the Russian Far East made a desperate and, apparently, completely hopeless attempt to communicate with the spacecraft, as if it had been in the Earth escape trajectory following a nominal burn of the MDU propulsion unit. Unnamed officials reportedly insisted on this "communication session," after reading on the Internet that some observers in Brazil had seen what looked like a firing of the probe's main engine. Obviously, nothing came out of this effort, except for more comments on the web about gross incompetence of the mission management. November 17 A small increase in orbital altitude of Phobos-Grunt was detected again between the 137th and 141th orbit of the mission. At the same time, the rocket stage, which delivered Phobos-Grunt into orbit, continued losing its altitude steadily. As before, this orbit change was attributed to the propulsive action of low-thrust engines onboard the spacecraft, which were apparently still receiving commands to maintain the attitude. As of November 17, several failure scenarios have been put forward, but none of them could be proven in the absence of telemetry from the spacecraft. According to one theory, erroneous data from BOKZ star sensors could interrupt the operation of the the main BVK timer (sequencer). BOKZ were obviously first to be blamed since they had been off (as planned) during the initial phase of the flight (when first and only telemetry was received), while all other systems seemed to be operating normally. However, the flight clock could also fail, as could a number of other systems. A combination of several failures was considered a strong possibility. Though mostly symbolic, the Phobos-Grunt mission objectives had to be officially abandoned, as the window of opportunity to send the spacecraft to Mars (in case it had stayed on the ground) closed on November 21. Despite persisting lack of official information, the disastrous mission still remained a popular topic in the Russian press, however many publications carried a mix of baseless hopes and innuendo, including ludicrous reports that the spacecraft did leave the Earth orbit in unknown direction and discussions of the "Russian curse" in the exploration of Mars. In the meantime, the Russian scientific community had to do a difficult soul-searching and pondering what to do next. Sources at the Space Research Institute, IKI, and one of its partners abroad told the editor of this web site that projects like Venera-D, Luna-Resurs and Luna-Glob (all relying on hardware developed for Phobos-Grunt) had remained on track and, as of November 20, there had been no immediate decision to stop any of them. As of the Russian return to Mars, most hopes were now riding with a European invitation to Russia to join the ExoMars mission... and save it from likely cancellation due to lack of funds. European Space Agency, ESA, directed its ground stations in Kourou, French Guiana; Perth, Australia; and Maspolamas, Canary Islands; to conduct last attempts to communicate with Phobos-Grunt on November 22. A total five communications sessions with a station in Perth were planned during consequent orbits of the spacecraft at 00:25, 01:57, 03:32, 08:16, 09:49 Moscow Time, each lasting six-seven minutes. A station in Kourou would have communication opportunities from 21:52 to 21:59 Moscow Time. One eyewitness in San Francisco described the spacecraft emitting flashes with peaks every 20 seconds -- a clear indication of tumbling. In the meantime, at 18:44 GMT, the second stage of the Zenit rocket, which flawlessly delivered Phobos-Grunt into its initial orbit, reentered the Earth atmosphere over Australia's Northern Territory. Unlike its payload, the stage's descent was steady and predictable. Remnants of the stage impacted the Earth surface at 22:47 at 22 degrees South latitude, 140 degrees East longitude, some 120 kilometers southeast of Dodger, Australia. November 23, Phobos-Grunt talks to ground control, finally! During the night from November 22 to November 23 Moscow Time (20:25 GMT on November 22), Phobos-Grunt finally communicated with a ground station in Perth, Australia, the European Space Agency, ESA, which operates the facility, announced. The contact was apparently established during first of five passes of the spacecraft over Perth from 00:25 to 01:11 Moscow Time. According to ESA, the critical communication session took place from 20:21 to 20:28 GMT on November 22, as the Perth station transmitted telecommands provided by NPO Lavochkin. A small, side antenna in Perth with a diameter of only 1.3 meters and rigged with a special cone was used to send a weak three-watt signal to the spacecraft, to turn on its transmitter. "Owing to its very low altitude, it was expected that our station would only have Phobos-Grunt in view for six to ten minutes during each orbit, and the fast overhead pass introduced large variations in the signal frequency," Wolfgang Hell, the Phobos-Grunt Service Manager at ESOC, was quoted by ESA web site. Despite these difficulties, it was a success: the signals commanded the spacecraft's transmitter to switch on, sending a signal down to the station's 15-meter dish antenna. Due to technical limitations of the ground station in Perth, it could only receive a carrier signal from the spacecraft containing no telemetry. Still, the reception of the signal confirmed that at least some radio systems onboard had been operational and provided hope that a full control over the mission could be established. Data received from Phobos-Grunt was then transmitted from Perth to Russian mission controllers via ESA's Space Operations Centre, Darmstadt, Germany, for analysis, ESA said. Even NPO Lavochkin, the spacecraft manufacturer, which has not provided any information on the mission since its launch, posted a message on its web site, saying that a "responding radio signal" had been received from Phobos-Grunt. During its successful contact with the Perth station, the spacecraft was in sunlight, while during communication attempts from Baikonur, Phobos-Grunt was in the shadow of the Earth. This factor could affect power supply to the communication gear, sources said. One source quoted by the press said that the facility in Perth could be reconfigured to receive telemetry from the spacecraft by the next pass of the probe within its communication range. The station's antenna range had already been expanded to facilitate communications with a low-flying vehicle. According to a representative of the European Space Agency, ESA, in Moscow, the spacecraft would be in the range of the same station in Perth on November 24 from 00:15 to 00:23 Moscow Time and from 01:48 to 01:56 Moscow Time. ESA then officially announced that additional communication slots had been available on November 23 at 20:21–20:28 GMT and 21:53–22:03 GMT. Around 01:00 Moscow Time (4 p.m. EST on November 23), a poster on the forum of the Novosti Kosmonavtiki magazine reported that the telemetry from the spacecraft had been received as well. A data set was reportedly downlinked to a European ground station and transferred to NPO Lavochkin for analysis. Shortly thereafter, the official Russian media quoted a European representative in Moscow as saying that ESA ground station in Perth had received telemetry from the spacecraft. According to Novosti Kosmonavtiki's Igor Lissov, an emergency telemetry frame from a radio-system onboard the cruise stage, PM, had been received, confirming normal power supply and the operation of the communication gear. During the next communication pass starting at 03:30 Moscow Time, ground controllers hoped to downlink telemetry via probe's main flight control computer, BKU, essentially a brain of the mission. During the day, Roskosmos and NPO Lavochkin reported that two communications sessions with Perth had been successful and resulting telemetry had been passed to the spacecraft developer. According to unofficial sources, all telemetry was unreadable, due to problems with coding and decoding data, possibly as a result of passing through an incompatible European decoding system. By default, the information from the spacecraft is coming in coded form, prompting ground controllers to plan sending specific instructions to the spacecraft to downlink data without encoding it first. Specialists also considered a possibility of downlinking information from the return stage, VA, however, its transmitters used a different frequency, which would require a separate effort. According to an ESA representative in Perth, quoted by RIA Novosti, five passes of Phobos-Grunt over Perth had taken place during November 24, beginning at 00:25, 01:57, 03:32, 08:16 and 09:49 Moscow Time. "The first pass was successful in that the spacecraft's radio downlink was commanded to switch on and telemetry was received," said Wolfgang Hell, ESA's Service Manager for Phobos–Grunt, "The signals received from Phobos–Grunt were much stronger than those initially received on 22 November, in part due to having better knowledge of the spacecraft's orbital position." ESA promised to continue its effort during November 24, to provide advice and assistance on possible communication strategies to consolidate the contact with the mission. Another five communication slots were available during the night of November 24–25, and the Perth tracking station was again to be allocated on a priority basis to Phobos–Grunt, ESA announced. Baikonur hears from Phobos-Grunt Also, on November 24, RIA Novosti reported that a Russian ground station in Baikonur, apparently manned by NPO Lavochkin telemetry specialists, was able to receive signal and telemetry from Phobos-Grunt, following its pass at 16:05 Moscow Time. In the meantime, Space Forces of Russia confirmed that Phobos-Grunt had been expected to reenter the Earth atmosphere in January-February 2012. At the time, the spacecraft was in a 319 by 205-kilometer orbit with an inclination 51.41 degrees toward the Equator. Radar data was now showing a steady decay of the probe's orbit, without previously seen minor increases in orbital altitude. When the first opportunity of the day to downlink telemetry from Phobos-Grunt came to ESA's station in Perth, nothing was heard from the spacecraft. According to ESA, the slots for communication, timed to coincide when Phobos–Grunt was passing over in direct line-of-sight with the station, began at 20:12 GMT and ran until 04:04 GMT. Each lasted just 6–8 minutes, providing very limited windows for sending commands and receiving a response. "Our Russian colleagues provided a full set of telecommands for us to send up," Wolfgang Hell, ESA's Phobos–Grunt Service Manager was quoted on the agency's web site, "and Perth station was set to use the same techniques and configurations that worked earlier. But we observed no downlink radio signal from the spacecraft." At the same time, ESA reported that observations from the ground had indicated that the orbit of Phobos–Grunt had become more stable. "This could mean that the spacecraft's attitude, or orientation, is also now stable, which could help in regaining contact because we’d be able to predict where its two antennas are pointing," said Manfred Warhaut, ESA's Head of Mission Operations at the European Space Operations Centre, Darmstadt, Germany, "The team here at ESOC will do their utmost to assist the Russians in investigating the situation." During November 26, the Perth station was expected to have four windows to communicate with Phobos-Grunt: 00:11 - 00:20 (with the spacecraft in the shadow during a part of the pass), 01:45 - 01:52, 06:30 - 06:38 and 08:04 - 08:12 Moscow Time. In the meantime, the spacecraft also reappeared over Baikonur, starting a seven-minute (or a less than 10-minute) pass within range of its tracking station at 16:00 Moscow Time, with the spacecraft on a daylight part of its orbit. However no news was released on the effort to communicate with the spacecraft, indicating a lack of progress. Still, Roskosmos representatives and the official Russian press reported that the telemetry data acquired previously had shown that Phobos-Grunt's main radio-system had been functioning and exchanging data with the main BKU computer. However the status of BKU was yet to be determined. According to reliable sources, ground controllers were continuing sending commands to Phobos-Grunt to downlink telemetry frames, as had been achieved earlier and, in addition, they were trying to downlink telemetry from the BKU flight control computer and sending commands to activate onboard rechargeable battery. Available telemetry from the BRK radio complex of the cruise stage yielded little information, an industry source said. An emergency telemetry frame did carry data on the condition of some components within BRK, for example, readings on the operational voltage and temperature of those components. It was also possible to conclude that a system for the exchange of data with the main BKU computer had been in operational condition. The data also contained a log of switches between a primary and a secondary transmitter. None of this information was essential for the analysis of the emergency situation onboard. Both Russian and US observations confirmed that the spacecraft had been maintaining its solar orientation. According to the Kommersant newspaper, in addition to analyzing available telemetry, engineers at NPO Lavochkin design bureau were working with their mission simulation hardware in an effort to uncover the source of problems with the spacecraft. According to a reliable industry source, specialists tested a theory that onboard star trackers, BOKZ, had either failed or had been giving out wrong information as the spacecraft had been acquiring correct orientation in the shadow of the Earth in preparation for the first engine firing on November 9. However a simulation of such failure failed to produce the kind of consequences, which had been seen in the actual mission, especially given the fact that the MDU propulsion unit could be activated via a backup command line. Another mystery of erratic appearance and disappearance of communications from Phobos-Grunt was attempted to be explained by the architecture of the power supply system, SEP. In case if solar panels stop supplying power and the onboard rechargeable battery discharge, the SEP switches to chemical source of power, KhIT, with a (non-rechargeable) half-day supply of electricity. Under such circumstances, the main rechargeable battery would be switched off, however the probe's power supply grid would be powered up only when the solar panels are exposed to the Sun. Obviously, power supply would stop in the shadow. As a result of the spacecraft flying in the emergency mode, the rechargeable battery might be staying off-line even when the solar panels were supplying electricity. (535) Although popular press was making wild proposals on the future plans for the Phobos-Grunt mission, the only realistic goal for ground controllers at the time was to receive useful information on the cause of its failure. If the culprit could be found and if critical systems onboard the spacecraft could be reactivated, attempts to establish some or even full control over the spacecraft would be made. Only then, it would be possible to consider what, if any, further steps could be made to continue the mission. Obviously, the first priority would be boosting the spacecraft to a higher, longer-lasting orbit, giving mission planners additional time to develop new flight scenarios. Depending on the probe's remaining resources and technical condition, it could be sent away from Earth for safety reasons and for testing or even aimed at one of potential destinations in the Solar System, such as an asteroid, the Moon or even Mars, for a flyby or some other abbreviated mission. As a very last resort, the spacecraft could be directed into the Earth atmosphere to burn up over an unpopulated area. All these options were long shots, given a complete lack of control over the spacecraft and only sporadic communications. All attempts to contact Phobos-Grunt from Perth on November 26 proved fruitless, after which ESA's ground station had to take a break in its effort, in order to support other missions. At the time, the facility was not scheduled to communicate with a stranded Russian probe until the night from November 28 to November 29. Although Phobos-Grunt did not respond to several latest radio requests for more telemetry, specialists at NPO Lavochkin prepared a new set of instructions for the probe to raise its orbit, the Interfax news agency reported. New commands would be sent to the spacecraft from Perth and Baikonur, apparently as one-way communications, in the hope that Phobos-Grunt would listen and execute the orbit-boosting maneuver. Odds of success of the latest effort were apparently very low, however, mission specialists decided to try this last-ditch effort in order to prolong the life of the spacecraft before its deorbiting and to extend communications windows with the spacecraft. A ground station in Baikonur was to have its first opportunity to contact Phobos-Grunt around 17:00 Moscow Time for about seven-eight minutes. However the spacecraft would be in the sunlight for only about half of that pass. During the night from November 28 to November 29, the ground station in Perth had five opportunities to contact Phobos-Grunt from 18:21 to 03:47 GMT (22:21 - 07:47 Moscow Time) However all attempts to command Phobos-Grunt to fire its engines for reaching higher orbit were unsuccessful, Russian news agencies reported, as industry sources promised to continue their efforts to communicate with the spacecraft. ESA reported that its ground station in Maspalomas, Canary Islands, had been in process of upgrades to add a "feedhorn" antenna similar to the one, which enabled the facility in Perth to communicate with Phobos-Grunt. In the meantime, ESA teams at ESOC center received a request from the Phobos-Grunt team to repeat attempts of uploading commands to the spacecraft to boost its orbit. In the meantime, reports surfaced that the US had not been able to assist Russia in tracking the Phobos-Grunt mission due to a policy issue associated with presence of a Chinese spacecraft onboard. Opportunities for communications with Phobos-Grunt on November 29:

After another fruitless day, Russian and European ground controllers continued their efforts to revive Phobos-Grunt on November 30. European mission control center in Darmstadt, Germany, announced that the ground station in Maspalomas, Canary Islands, had been ready to start sending commands to the spacecraft around 14:30 GMT. The commands which were sent around 14:35 GMT were designed to turn on the transmitter onboard the spacecraft, however, yet again, there was no response. ESA said that Maspalomas station had been still in process of modifications and available power of transmission had been very low. The commands to the spacecraft to activate its downlink and send telemetry were to be repeated around 12:47 GMT on December 1, when last modifications to the facility were to be completed. In the meantime, the ESA station in Perth was scheduled to send commands during evening passes (see table below) of Phobos-Grunt to activate its thrusters for an orbit-correction maneuver. Opportunities for communications with Phobos-Grunt on November 30:

The European ground station in Maspalomas joined the effort to contact Phobos-Grunt on December 1 with two attempts, however still nothing was heard from the spacecraft. A station in Perth planned to send commands too, but ESA reported less than favorable conditions: during one pass, the spacecraft would be totally in darkness (and therefore likely without power), during another -- only with limited sunlight, while two passes in the daylight would not be optimal for pointing the antenna. Opportunities for communications with Phobos-Grunt on Dec. 1:

ESA reported that attempts to send commands to Phobos-Grunt from Perth made at 01:02 GMT and from Maspalomas at 02:12 had been unsuccessful and further attempts to contact the probe would be stopped. In the meantime, the spacecraft was slowly losing its altitude: the apogee (the highest point of the orbit) descended from 345 kilometers following the launch on November 9 to around 308 kilometers; while the perigee following a slight boost from original 204 kilometers to around 206 kilometers between November 18 and November 21, then decayed to 203 kilometers. Opportunities for communications with Phobos-Grunt on Dec. 2:

According to US radar data, two objects apparently separated from Phobos-Grunt on November 29 (around mid-day) and on November 30. Both objects apparently slowly drifted away from the main spacecraft, then quickly lost the altitude and at least one of them reentered the Earth atmosphere on December 1. Available radar data enabled a prominent satellite observer, Ted Molzcan, to make a conclusion about relatively high density of one piece and estimate its size at 0.1 meters and mass at around 0.5 kilograms. Opportunities for communications with Phobos-Grunt on Dec. 3:

As last hopes for recovering Phobos-Grunt faded and the Internet gossip focused on the reentry of the spacecraft, industry sources reported that Russian space agency, Roskosmos, had made another request to the European Space Agency, ESA, for assistance in tracking the mission. According to ESA, a 15-meter antenna in Maspalomas, Canary Islands, would be used to send commands to the spacecraft. In the meantime, within last two days, witnesses on the ground reported seeing Phobos-Grunt changing its brightness, suggesting tumbling in orbit as fast as one revolution in 20 seconds. At the time, the reentry of Phobos-Grunt into the Earth atmosphere was expected around January 12, 2012. ESA announced that following a request from Russian space officials, ESA had continued its efforts to communicate with Phobos Grunt via the agency's Maspalomas tracking station. However all communication attempts from December 5 through December 7, which made use of a redundant transmitter on board the spacecraft, did not succeed, ESA said. The agency has agreed to continue the effort until Friday, December 9, 2011. In the meantime, a rare Russian reaction to the Phobos-Grunt fiasco came from Viktor Khartov, the head of NPO Lavochkin design bureau, which developed an ill-fated probe. In an interview with the Izvestiya newspaper, Khartov had confirmed known circumstances of the Phobos-Grunt's short-lived mission and its failure in orbit, but refuted "unnamed experts" widely quoted by popular press claiming that the spacecraft was unable to maintain its attitude toward the Sun and was tumbling in space. (In reality, ground-based images of the spacecraft, which were quoted by "experts", did not provide any definitive information on the status of the mission.) "Those images of the spacecraft in orbit that we were able to obtain show that noticeable tumbling of the spacecraft had not been taking place," Khartov said, "...we have no information when and why the nominal flight sequence had been interrupted... but we've got one sure fact: the spacecraft had been oriented toward the Sun and onboard computer had performed its functions. Possibly, it is still in this mode and we will continue attempts to revive it." Still, Khartov did essentially admit that the Phobos-Grunt project had been too ambitious for the current state of the nation's planetary program. He called for the resumption of the Russian deep-space exploration with lunar missions, such as Luna-Resurs and Luna-Glob, which had been previously approved by the Federal space program. However critics already said that without a major re-design of the flight control system, which Luna-Resurs and Luna-Glob would inherit from Phobos-Grunt, lunar missions would share a similar fate. ESA made two attempts to communicate with Phobos-Grunt on December 8 without success. At least two more attempts were expected on December 9. Opportunities for communications with Phobos-Grunt on Dec. 8:

Phobos-Grunt launch milestones for Nov. 8-9, 2011:

Next chapter: Phobos-Grunt reentry

Page author: Anatoly Zak; Last update: December 10, 2011 Page editor: Alain Chabot; Last edit: November 9, 2011 All rights reserved |

IMAGE ARCHIVE A Zenit rocket with Phobos-Grunt awaits its historic liftoff shortly after its rollout to the launch pad on November 6, 2011. Credit: Roskosmos A Zenit with Phobos-Grunt on the night of the fateful launch on Nov. 9, 2011. Credit: Roskosmos

First live TV images of the Zenit rocket with Phobos-Grunt spacecraft hours before scheduled liftoff Tuesday. Credit: TsENKI

The Zenit rocket during fueling. Credit: TsENKI

A Zenit rocket with the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft lifts off shortly after midnight on Nov. 9, 2011, Moscow Time. Credit: TsENKI TV (top) and Roskosmos photo. A close-up map of the Phobos-Grunt trajectory during the first engine burn. Credit: IKI A close-up map of the Phobos-Grunt trajectory during a second engine burn of the mission designed to push the spacecraft from the Earth orbit in a direction of Mars. Credit: IKI A schematic illustrating the initial phase of the Phobos-Grunt mission relative to the Earth surface. Credit: Roskosmos

View of the Perth 15m antenna showing the feedhorn antenna mounted near the small, 1.3m search antenna, both mounted at the side of the main dish. The mini-antenna was used to send telecommands to Russia's Phobos-Grunt mission in Earth orbit on 22 November 2011. Credit: NASA

ESA's Perth station is located 20 kilometres north of Perth (Australia) on the campus of the Perth International Telecommunications Centre (PITC), which is owned by Telstra, and operated by Xantic. Credit: ESA The main and a secondary (top center) antennas in Perth, Australia, which had succeeded on Nov. 23 in receiving first signals from Phobos-Grunt mission since its launch on November 9, 2011. Credit: ESA ESA'a ground station in Maspalomas, Canary Island. Credit: ESA A photo of the Phobos-Grunt taken from the ground on November 29 seems to confirm that the probe's solar panels were deployed (center). The MDU propulsion unit can be seen on the left, the Earth return vehicle is on the right. Copyright © Ralf Vandebergh. Published here with permission.

An artist rendering of the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft stranded in the low Earth orbit. Copyright © 2011 Anatoly Zak Viktor Khartov, the head of NPO Lavochkin design bureau, which developed an ill-fated probe, gave a rare interview to a Russian paper on Dec. 8, 2011. Copyright © 2010 Anatoly Zak

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||