More on Phobos-Grunt: Project developments in 2004-2009 Command and control challenges in Phobos-Grunt mission In the aftermath of Phobos-Grunt Searching for details: The author of this page will appreciate comments, corrections and imagery related to the subject. Please contact Anatoly Zak. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

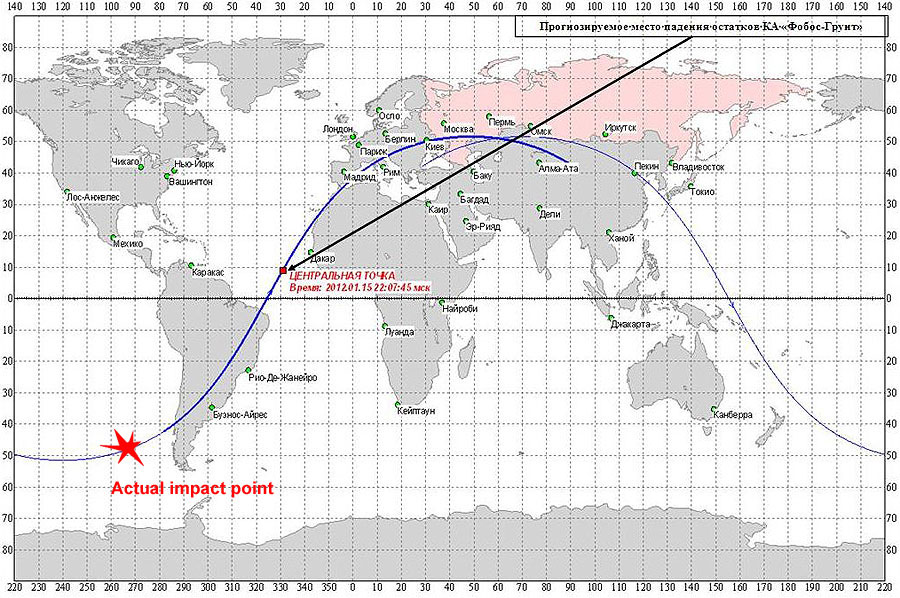

Above: An official map of the Phobos-Grunt reentry released by Roskosmos by 20:00 Moscow Time on Jan. 15, 2012. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Previous chapter: Phobos-Grunt reentry Information on Phobos-Grunt failure emerges A plausible scenario for quick demise of Phobos-Grunt leaked from industry sources to the online forum of the Novosti Kosmonavtiki magazine on January 17. The most likely culprit in the failure of the probe's propulsion unit to ignite soon after it had entered orbit on November 9 was a programming error in the flight control system. Post-failure tests (apparently simulating in-flight conditions) revealed that the processor usage level in the main flight control computer onboard the spacecraft exceeded 90 percent of its capacity. It could easily lead to crashes and rebooting as more systems were being activated after the spacecraft had left the range of Russian ground control stations after reaching orbit. Among those systems were star trackers (used for attitude control in the shadow of the Earth) and a Chinese satellite. In the meantime, the power supply system onboard the spacecraft worked flawlessly. Following the initial failure, as ground controllers apparently succeeded in activating the X-band transmitter onboard the spacecraft, new problems arose. The device would transmit a signal with a power of around 40 watts, however its own operation would consume around 200 watts. The deactivation of the transmitter was not taking place when the spacecraft was flying in the shadow of the Earth for prolonged periods of time. As a result, the probe slowly drained its rechargeable power batteries and then its emergency power source, known as KhIT, leading to a complete failure of all onboard systems on November 28, 2011. Investigative commission conclusions In the last week of January, another industry source leaked more critical details of the investigation into the Phobos-Grunt failure. This information was based on the conclusions of the sub-commission No. 2, which investigated the behavior of the probe's flight control system, BKU, during the ill-fated mission. The BKU system had been essentially a brain of the spacecraft and its shortcomings had been well documented long before the ill-fated launch. As a result, the work of sub-commission No. 2 was the most critical part of the investigation, formulating the most probably cause of the failure. In its summary report, the group concluded that the loss of the mission failure was the result of the design error and the lack in the ground testing of BKU. According to the report, after the spacecraft reached the orbit, all systems worked well. Ground controllers did not receive a signal confirming the opening of solar panels, however, the investigation showed that this confirmation had been been included into the telemetry stream relayed to the ground before the launch. Still, the data about electric current in the power supply system did confirm indirectly that panels had deployed. During the third orbit, no data had been received about the ignition of the Main Propulsion Unit, MDU, and all following operations of the pre-programmed flight sequence and the activation of the radio-transmitters. The most probably cause of this failure was a simultaneous rebooting of two operational processors in the main computer Central Calculation Machine, TsVM-22. The computers could crash as a result of errors in their software or as a result of some external reasons, such as electromagnetic incompatibility, industry sources said. The mentioning of this last point in the report apparently became a basis for numerous reports in the Russian press blaming the failure on various improbable external reasons, such as foreign radars or solar flares. However around mid-January, NPO Lavochkin did conduct a series of tests to see if BVK could be affected by interference from the probe's own power supply system or from unlikely external sources, such as a narrow powerful beam of a ground radar. During these tests, the computer withstood all simulations without any problems. With all external failure scenarios effectively debunked, the most probable cause of the failure was narrowed down to the lack of integrated testing. Following the initial failure to initiate the flight sequence, the mission simply lacked any available scenario to communicate with the spacecraft in the low Earth orbit or to reboot its computers by a remote control. The commission also established that the existing pre-programmed flight sequence had not required a confirmation of the correct attitude control prior to the firing of the MDU to escape Earth orbit. As a result, the wrong orientation of the probe during this critical maneuver (if it ever took place) could potentially lead to the mission failure. (544) The investigative commission completes its work In the meantime, the official Russian media reported that the Chairman of the interagency commission investigating the Phobos-Grunt failure had handed in the official results of the body's work to the head of the Russian space agency, Vladimir Popovkin on the evening of January 30, 2012. (545) The final report was previously promised to be delivered to the agency's leadership four days earlier. On Feb. 3, 2011, Roskosmos publicly released "main conclusions" of the commission's findings. The commission evaluated more than 700 documents related to the development of the Phobos-Grunt project and all aspects of testing, launch and flight of the probe. The commission analyzed available telemetry data, which was received at the initial phase of the flight via the NIK Fregat ground measurement complex, as well as the telemetry received via X-band ground stations on Nov. 22-24, 2011. The document confirmed that during the first two orbits and until 01:10:28 Moscow Decree Time on Nov. 9, 2011, the mission had been proceeding normally. The only anomaly detected at that stage was the lack of confirmation that the solar panels had been fixed in open position. The opening itself had never been in doubt, Roskosmos said. (Editor's note: As it was reported before, a normal power supply onboard confirmed that panels were in open position.) Following the emergency situation onboard the spacecraft, the spacecraft entered "constant solar orientation" flight mode, known as PSO, as required by the logic of the spacecraft operation. The "power balance" was maintained onboard until Nov. 24, 2011, Roskosmos said, confirming previously known information. The interruption in the power supply started beginning on Nov. 24, Roskosmos said, also confirming previous reports. The agency did say that by November 29, all resources of the rechargeable battery and of the emergency chemical battery, KhIT, had been exhausted. Sometimes before that, possibly on November 27, the spacecraft switched to the minimum power supply mode, Umin2. Also, KhIT battery lost pressurization, which manifested itself in the form of two fragments separating from the space and detected by US tracking assets. Roskosmos also confirmed that small changes in orbital altitude of the spacecraft had been the result of the attitude control thrusters firings to maintain the solar orientation. Finally, Roskosmos confirmed the loss of power supply had led to the failure of the flight control system. A periodic activation of the flight control system, BKU, and the flight control had only been possible in sunlight, when solar panels had been exposed to the sunlight, the agency said. Looking for a culprit In the effort to find exact cause of the emergency situation onboard the spacecraft the investigative commission analyzed possible hardware failures and possible interruptions of the pre-programmed flight sequence of the onboard flight control system, BKU, Roskosmos said. Several components of the spacecraft came under scrutiny as possible culprits in the emergency onboard:

According to Roskosmos, the expert analysis ruled out the possibility that any of these systems could have become the source of the accident. Instead the emergency situation onboard had been caused by a restart of two semi-sets (processors) of the TsVM22 computer in the onboard calculation complex, BVK, Roskosmos said. As a result of such "dual restart," the nominal pre-programmed flight sequence was interrupted and the spacecraft entered solar orientation, simultaneously waiting for ground commands in X-band frequencies. However the spacecraft was designed to communicate in X-band only during the cruise stage of the flight (between the Earth and Mars, following the escape from the Earth orbit), Roskosmos admitted. The most likely factor which caused a "double restart" was a local influence of heavy charged particles from space, Roskosmos concluded. This influence led to errors in the random-access memory modules, OZU, in the TsVM22 computer during the second orbit of the mission. Errors in RAM modules could be caused by intermittent interference caused by heavy space particles on particular cells in computer modules, which contain two chips of the same type -- WS512K32V20G24M. The influence of heavy particles caused a distortion of the computer code and activated a "guard" timer, which in turn triggered a reboot. Existing certification documents do not regulate the particular model of heavy particle influence, Roskosmos said. The investigation commission recommended to develop and implement new certification guidelines which would contain updated models of ionized radiation in space. According to Roskosmos, the interagency commission also evaluated other factors which could cause a "dual restart" of TsVM-22:

Simulating the failure In January 2012, NPO Lavochkin used its integrated stand of the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft to model possible electromagnetic influence and programmatic errors on the operation of the flight control system. However none of these scenarios could be recreated, the agency said.

Long before the launch of Phobos-Grunt, it was known that the mission was doomed to failure due to inadequate flight control and communications systems. Still, after the spacecraft did fail, many "external" reasons for the fiasco were fielded by various sources in an obvious effort to shift the blame away from the engineering mismanagement of the project:

Next chapter: Phobos-Grunt-2

Page author: Anatoly Zak; Last update: April 5, 2012 All rights reserved |

IMAGE ARCHIVE

An artist rendering of the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft stranded in the low Earth orbit. Copyright © 2011 Anatoly Zak

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||